A risky combination

I greatly appreciate the invitation to contribute biweekly to The Mexico Brief. Since this is my first piece, I’d like to dedicate it to reviewing the current state of Mexico’s economy. Virtually all of the data we have predates Donald Trump’s arrival at the White House, though some indicators are more recent and may already reflect part of the impact of the decisions he has made.

From 1980 to 2018, the Mexican economy grew at an average annual rate of 2.2%, despite the domestic and foreign crises experienced during those 38 years. However, beginning in 2018, there is a clear shift in trend. The cancellation of the construction of Mexico City’s new airport had an immediate effect on market confidence, which was reflected in a depreciation of the peso and a rise in interest rates. During 2019, that decision was compounded by the obstruction of the ongoing energy reform, and investment steadily declined throughout the year. Before COVID and the lockdown arrived, there was already a contraction - reaching -1% in the last quarter of 2019 and -2% in the first quarter of 2020, although the final days of that period can already be considered part of the pandemic’s impact.

Unlike most other medium and large countries, Mexico implemented no support programs for businesses or families to navigate that period. Perhaps for this reason, the 2021 recovery was weaker than elsewhere. By the end of 2021, the Mexican economy was 1.5% smaller than at the end of 2019, meaning that López Obrador’s first three years in office resulted in a -2.5% contraction.

But then came the miracle. In 2022, contrary to forecasts, the Mexican economy grew 3.7%, and in 2023 it nearly repeated that figure, reaching 3.3%. This positive dynamic lasted through July 2024, and this helps explain why. In 2021, after the weak data mentioned above, López Obrador lost the midterm election and was only able to retain a majority due to the opposition’s lack of unity. However, this majority was smaller than the one he had held since 2018.

Unwilling to risk losing the 2024 presidential election, he immediately ramped up public spending. Until the midterm, government spending stood at 23% of GDP. In the second half of 2021, it had already risen to 24%. In 2022 it averaged 24.3%, 25% in 2023, 26.2% in the election year, and in the first quarter of 2025 it has already reached 27% of GDP. Since revenues haven’t grown at the same pace, the government deficit, which stood at 2% of GDP before the 2021 election, now exceeds 4%, and using the broader measure of public sector financial requirements, the increase over the last twelve months is 5.5% of GDP.

To ensure victory in the 2024 election, a bubble of income was created through cash handouts in the form of scholarships and pensions, as well as through unnecessary and ostentatious public works projects. It worked, because López Obrador’s party won the election - but in the process, the increase in spending, reflected in growing debt, took on a life of its own: the cost of financing the debt has risen so quickly that, even with a contracting economy, the deficit continues to grow.

It is very clear that the Mexican economy is in contraction, and for internal reasons. Before Trump’s decisions, consumption - which had been growing at an annual rate of 5% from the midterm through the presidential election - had already plummeted to 1% (February 2025). Investment, inflated by a fictitious bubble we’ll discuss another time, reached 20% growth in 2023, but as of February, it is at -6% annually.

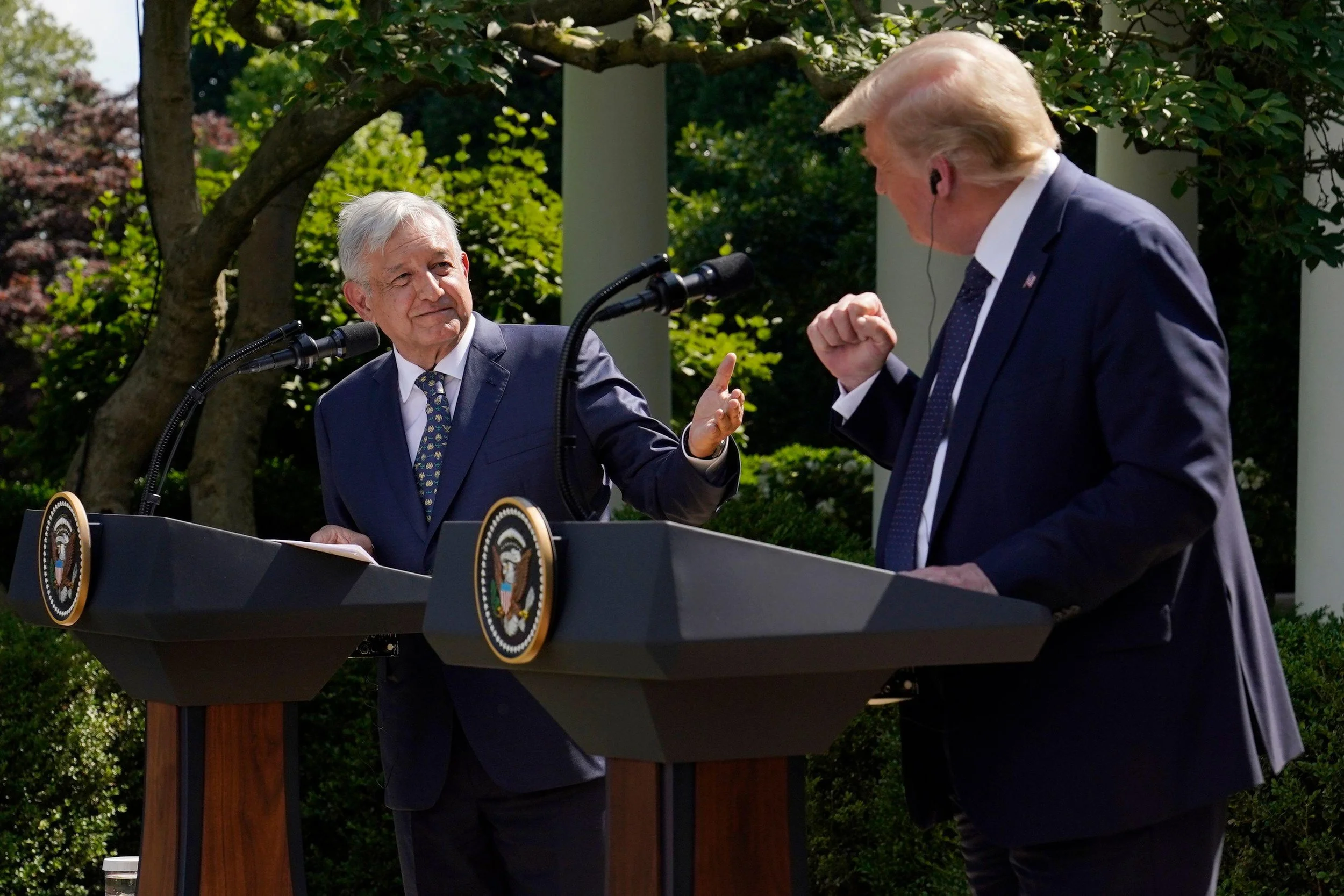

López Obrador’s poor decisions - beginning with the airport cancellation - weakened the country’s economic momentum; the excessive election-driven spending left public finances in a vulnerable position. Thus, Mexico finds itself in recession, but with a government deficit that is no longer easy to finance responsibly. It was in these conditions that Trump arrived at the White House. Not the best combination.

Editor’s note: Macario Schettino was Professor of the School of Government at Monterrey Institute of Technology from 2015 - 2024. He writes regularly about Mexico’s economy and politics for El Financiero and other publications.