Diego Vega Solorza: rewriting the language of dance

by Ambika Subra.

If you walk past a Mexico City park on a Saturday morning, you’ll likely see couples twirling to cumbia and salsa, their feet moving to rhythms passed down through generations. Movement is woven into the city’s fabric, a language of joy, spontaneity, and connection. But choreographer Diego Vega Solorza is not interested in dancing through time - he is interested in slowing it down and forcing us to sit inside its weight. His work does not unfold in bursts of rhythm but in suspension, where every gesture lingers, where movement becomes a living archive.

Vega Solorza is reshaping Mexican contemporary dance, rejecting the institutional validation that has long defined it. In a country where dance is often tied to folkloric tradition, he carves out a third space - one that refuses Eurocentric virtuosity and treats movement as a form of writing. His performances do not chase spectacle but command attention through stillness, through contrast, through the radical act of taking up time and space.

His latest work, Canto de Agua, presented at Galería LLANO in collaboration with Don Julio, embodies this philosophy. The performance is not just about water; it is a confrontation with how it is controlled, extracted, and fought over. The dancers, immersed in Rafael Durand’s live score and framed by Fernanda Caballero’s painted backdrop, move at an almost impossible pace—slow, deliberate, and fluid, as if suspended in water itself. Their movements demand patience, breaking the expectation that dance must entertain through speed. Canto de Agua transforms dance into a political act, where the body mirrors the fragility, resilience, and exploitation of natural forces.

Vega Solorza’s work flows between the political and the spiritual. Destellos de Luz, his previous collaboration with composer Dario afb, explores this balance through two opposing dancers in dialogue. One is soft and playful, the other sharp and assertive. They do not seek to merge but witness and admire each other’s differences, creating a tension that is as intimate as it is unpredictable. When they do align, the moment is rare and electric, dissolving as quickly as it forms. Their separation is just as powerful as their unity, turning the performance into a meditation on trust, distance, and the evolution of duality in space.

Vega Solorza’s work rejects the rigid hierarchies of classical dance, choosing instead to work with performers of all body types, identities, and backgrounds. His choreography does not rely on formal technique but on how people carry weight, how they inhabit space, how they move through a world that often demands they shrink themselves. He does not see dance as something to be perfected but as something to be written, rewritten, and preserved through repetition and memory.

"Nothing in my work is accidental. There are chronometers and counts, but there is no script," he explains.

Vega Solorza is building a new framework for contemporary dance, one that thrives outside the canon in Mexico City’s independent art and performance scenes. By expanding dance into visual art, music, and radical social and spiritual critique, Vega Solorza is not just shifting how dance is performed - he is reshaping how we experience time, movement, and human connection. His work demands patience. It demands attention. And in a world that is constantly moving faster, it reminds us of the power in slowing down, in witnessing, in waiting.

Mabe Fratti and the new sonic vanguard

by Ambika Subra.

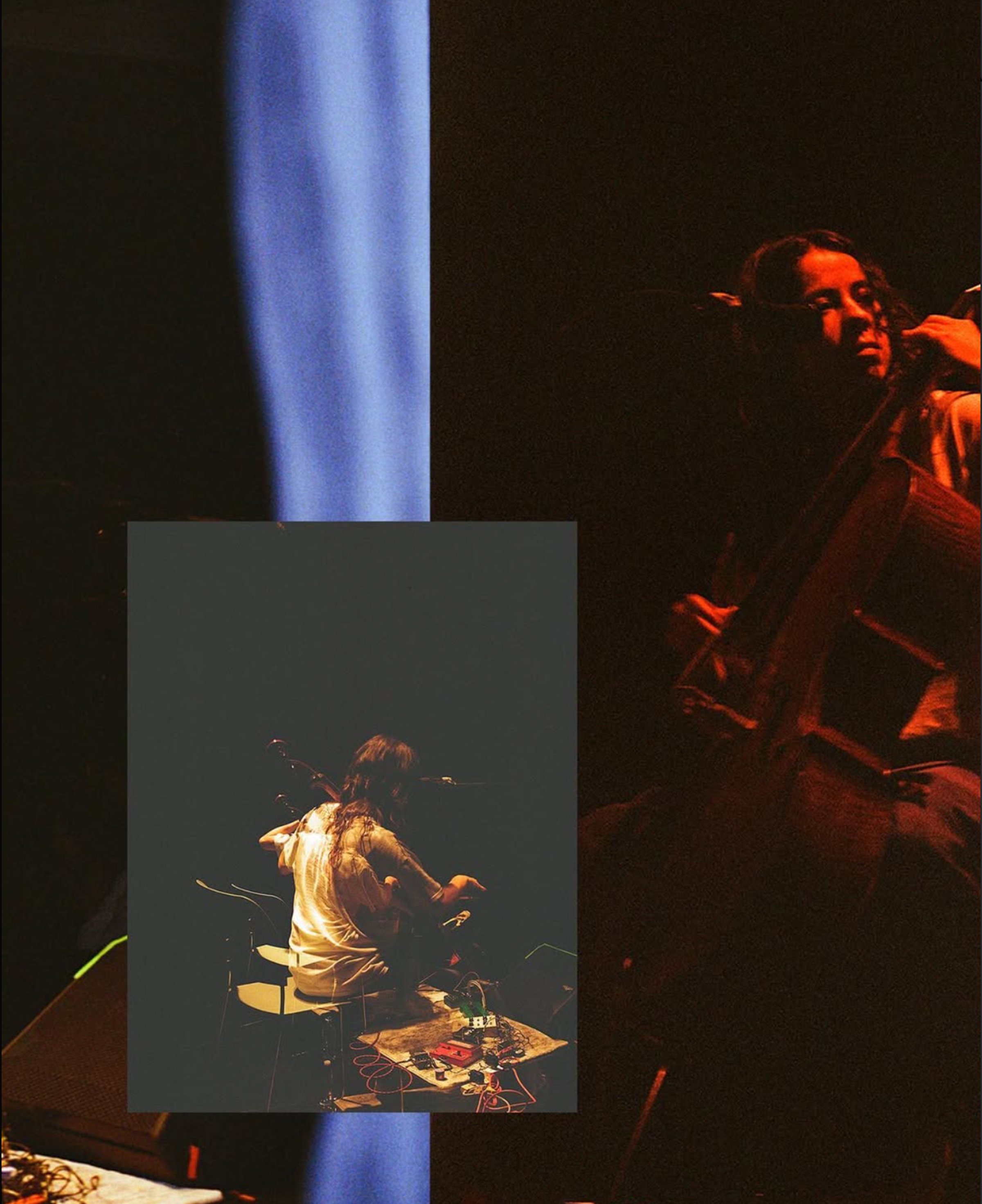

Amidst the horizontal vertigo of Zona Maco, where Mexico City’s galleries and restaurants overflow with collectors and influencers, something unexpected happened underground. Experimental cellists Mabe Fratti and Lucy Railton performed for a packed crowd of young Mexicans in the basement of the Jean Paul Gaultier showroom. Far removed from the spectacle of art commerce and spectacle, the cellists cut through the noise—an urgent exchange that redefined the cello’s role as a vessel for reinvention.

Mabe Fratti, Guatemalan-born and Mexico City-based, has been reshaping Mexico’s sonic landscape for the last decade. Her work blends composition and improvisation, intertwining the cello’s deep resonance with voice (in English and Spanish), electronic sounds, and unconventional plucking techniques. Once bound to orchestras and academia, Fratti reclaims the cello in experimental spaces, drawing full crowds and defying classical constraints. Her fluid, immersive approach expands the instrument’s vocabulary beyond its traditional lineage, much like Arthur Russell or Joanna Newsom.

Kuboraum-Innerraum and Tono Festival orchestrated this performance of Fratti and Railton—a rare convergence in the chaos of art week. Its salience was in its sonic alchemy—where classical instrumentation became a living, evolving force within Mexico’s underground. Here, the cello wasn’t an emblem of European high culture but a connective vessel of cross-border existence. Fratti and Railton didn’t just challenge tradition; they reframed it entirely for our contemporary. The music, swelling and unraveling in unpredictable waves, mirrored the cultural tensions outside—where Mexico City’s cosmopolitan sheen often masks a local underground scene pulsing with subversion.

This isn’t merely a stylistic evolution; it’s a philosophical shift reflected in Mexico City’s multicultural landscape. The embrace of classical instruments in the experimental scene speaks to a broader movement of young Mexicans and the artists settling in Mexico from abroad—resisting colonial baggage and establishing a third culture that does not abandon the past.

Mexico City’s artistic landscape thrives on inherited forms and contemporary reimaginings. As globalization accelerates cultural exchange, young artists are transforming these influences into something distinctly their own. For Fratti, this means erasing the line between performer and instrument, embracing her Guatemalan birth and her Mexican identity, and allowing voice, electronics, and tactile playing to merge into something raw and unfiltered. Her collaborations—whether in the haunting textures of Titanic, her project with Héctor Tosta, or the stark intimacy of her 2022 solo album Se Ve Desde Aquí—defy categorization.

“If I don’t know who I can be, then I am my feeling,” Fratti declares in the opening track of Vidrio, her collaborative album with Tosta (also known as I La Católica). Released under the moniker Titanic, Vidrio was one of three albums Fratti released in 2023, a testament to her restless creative energy and widespread resonance. Whether in solo work or collaborations, her music is rooted in transformation—of sound, of self, of the structures that define musical expression.

Here, the underground’s adoption of classical techniques isn’t nostalgia; it’s about reclaiming sound as something fluid, immediate, and unbound by expectation. It is the soundtrack of young creatives redefining the landscape in Mexico today. The cello, in the hands of Mabe Fratti, is neither an artifact nor a novelty, but a force—urgent, alive, and attuned to the city’s evolving pulse.

What lies beneath: the living archives of Lorena Mal

by Ambika Subra.

Unearthing the hidden narratives beneath our feet, Mexican artist Lorena Mal is revealing the deep entanglements between land and power. She is an excavator—not only of the earth’s soil and trees, but of the knowledge systems, political structures, and forgotten narratives embedded within it. Working across sculpture, performance, and archival intervention, Mal dismantles the illusion of landscape as a neutral backdrop. Instead, she exposes it as a charged site of conflict, migration, and resilience, shaped by forces both geological and geopolitical. One of the most exciting voices in contemporary Mexican art, her recent works at the XV Bienal FEMSA and Museo Jumex have cemented her place as a radical force in rethinking our experiences of landscape.

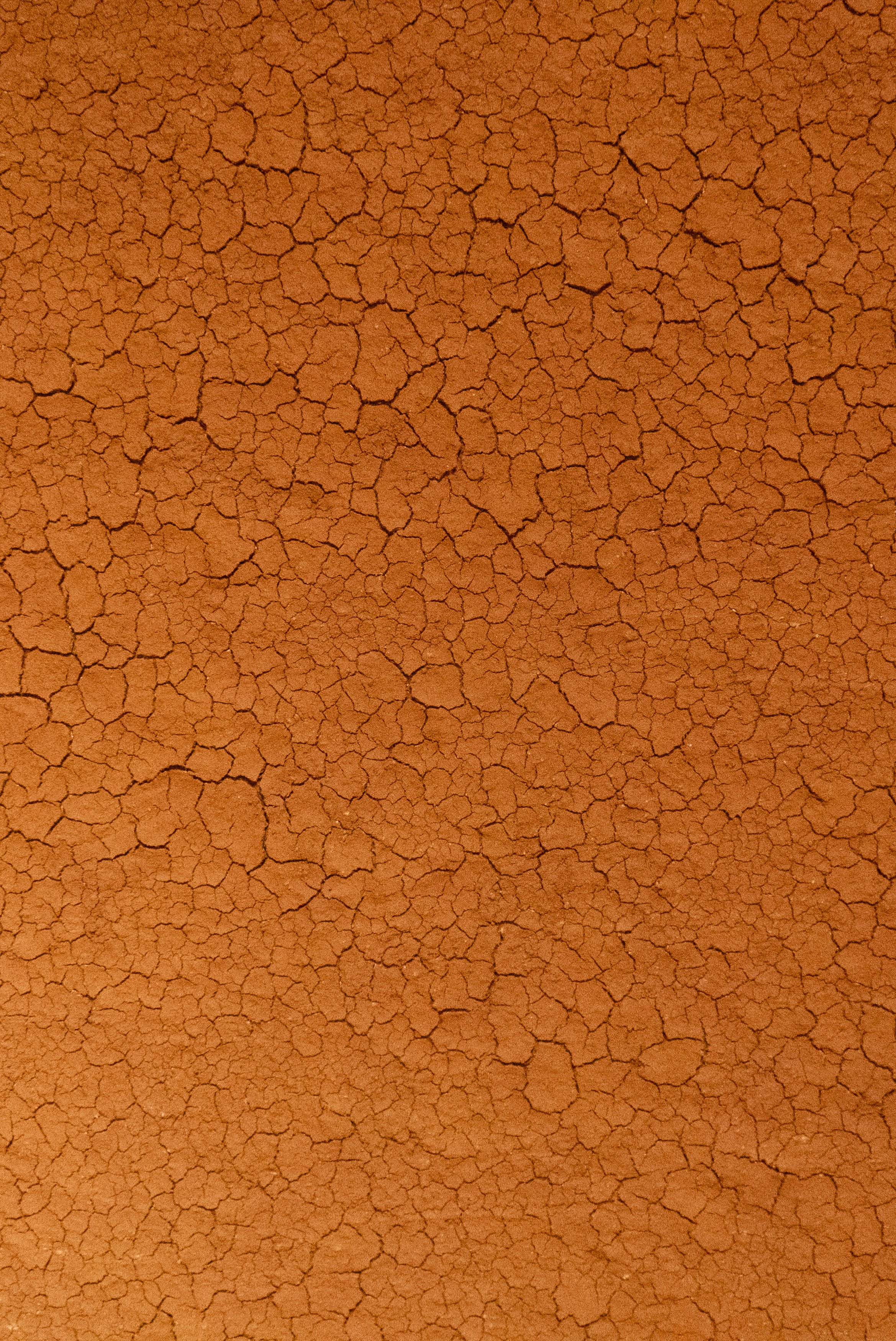

Mal refuses to see land as separate from history. In Restregarnos Tierra en los Ojos, an installation commissioned for the XV Bienal FEMSA, she created an archive of occupation and displacement by covering the space’s surfaces with soil—a raw, living material applied in a fermented state, allowing microbial life and air to bind it into a clay that naturally cracked and shifted over the four months of the exhibition. Sourced from the Bajío, the soil bore the region’s long past of floods and droughts, colonial mining extraction, and environmental destruction. Who has the right to a land? Who determines its fate? Mal’s intervention blurred the lines between architecture and archaeology, embedding the region’s instability directly into the walls of the exhibition. The soil itself became testimony—not just a metaphor, but an active record of conflict, survival, and resistance.

Beyond the visible, Mal’s work listens. In Largo Aliento, performed at Museo Jumex this past year, she translated tree rings into sonic compositions, using instruments made from those trees as a vehicle for a deep, resonant breath. Just as the soil preserves and reveals the memory of land through its raw materiality, Largo Aliento treats breath as a conduit for memory, where tree rings vocalize their silent histories. These rings, like layers of sediment, hold the imprints of environmental upheavals—fires, droughts, cycles of violence and renewal. By playing their breath, Mal does not impose a structure onto their histories but coaxes out their latent recollections, turning them into sound. Her instruments do not adhere to tempered scales or fixed notation, but instead respond to human interaction. This relationship resists linear time in favor of something more fluid and horizontal, creating a resonance that blurs the boundary between past and present. Both earth and breath become modes of listening—fragile yet persistent archives of what landscapes remember.

History is not confined to human narratives alone. At its core, Lorena Mal’s work is about destabilization—of narrative, of power, of our very understanding of place. She is not interested in transformation as a fixed act but in how landscape holds and reveals its own records through its raw architecture. Mal excavates how land bears witness to colonial displacements, migrations both human and botanical, and the erasure embedded in plantation histories. By blending materials across geographies, carving new sonic pathways through time, and forcing us to confront what lies beneath our feet, Mal reframes the land as an active force—one that remembers, resists, and refuses erasure. Her practice is not simply an exploration of landscape; it is a reconfiguration of how we engage with the world itself.

re/presentare is rewriting the role of architecture in Mexico

by Ambika Subra.

In Mexico, power is etched into the streets—highways slice through working-class neighborhoods, glass towers rise from Indigenous communities. Architecture in Mexico can serve as both a weapon and a witness to inequality. But re/presentare, a new spatial research agency in Mexico City, based at UNAM, is attempting to flip the script. Founded by architects Sergio Beltrán-García and Elis Mendoza, and working as part of Investigative Commons - a network of agencies around the world using open-source methods to investigate human rights abuses - re/presentare is moving beyond analyzing space. Its architects are trying to reimagine space as a tool for justice, hope, and collective action. This year, with the launch of their first major socio-environmental investigation in Mexico City, their work is set to establish a new benchmark for spatial research and intervention.

“Architecture is the discipline of organizing bodies,” Beltrán-García says. “You can pass here; you cannot pass there. And that means power.”

Both Beltrán-García and Mendoza were trained by Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture, the renowned London-based investigative group based at Goldsmiths, University of London. But while Forensic Architecture excels at producing analytical data sets for the purposes of exposing state and corporate violence, re/presentare looks to go a step further—into direct intervention and localized action. Their goal is not just to diagnose problems but to collectively repair and redesign spaces to amplify communities over individuals and capital.

One of re/presentare’s first major investigations is taking place in Xochimilco’s San Gregorio Atlapulco, a pueblo originario where locals have been resisting water privatization and urban expansion for several years. Beyond research, the team is working in collaboration with the community to develop methods for investigating the violence they have faced at the hands of the state, including the erasure of their collective traditions. “Investigating collectively,” Mendoza emphasizes, “is just as important as resisting collectively.”

In this way, it’s helpful to understand them not just as architects but as storytellers. They’re using design to make invisible violence visible. “The violence is in the silence,” Mendoza says. “Our job is to force it into the light.” Re/presentare is developing a new vocabulary of resistance through physical and digital interrogation: How do you map the chaos of social media, YouTube comments, or the calculated rhetoric of a morning press conference? How do you make power visible?

Solutions come through building networks. With their work in Xochimilco, alongside local land and water defenders, a model of cooperation is forming that challenges architecture’s often individualistic and hierarchical structures. It’s a horizontal approach which lays groundwork for future expansions, such as collective exhibitions with other spatial practitioners—architects, artists, and individuals from entirely different disciplines. “It’s not enough to analyze what we see,” says Beltrán-García. “We also have to visualize it, to make it tangible in museums, workshops, and public forums.” Through workshops, collaborative design projects, and on-the-ground interventions, re/presentare is creating a new kind of research practice—one that merges community engagement with the transformation of public space.

Mexico is a country facing acute problems with gender violence, environmental destruction, and authoritarianism, all of which is reshaping the country’s physical and built environment. re/presentare is working to imagine and build alternative futures. “The only way to build the future we want,” Mendoza insists, “is by strengthening our networks. By working together.” With this upcoming investigation in Mexico City, their practice holds the power to flip the script—turning Mexico’s struggles into strength via its collective action. In the face of overwhelming challenges, re/presentare is paving the way for another possible outcome where space is not a tool of oppression, but a canvas for hope.