Mexico City’s MUAC is a hub for sonic experimentation

by Ambika Subra.

Mexico City has more museums than any other city in the world. Whether conceptual or commodified, contemporary art can be found in every colonia. But the seed of contemporary art lies in its debate, which is why one of the city’s most vital cultural gems sits not in a gallery district or a downtown corridor, but on the campus of UNAM. What sets El Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) apart in the Mexican museum landscape is its Espacio de Experimentación Sonora (EES), a room designed exclusively for experimental music. It offers more than a space for sound. It creates the conditions for deep listening. Its architecture invites not spectacle but study. It is a purpose-made environment for sonic research, where artists stretch time, distort history, and activate archives in ways that traditional exhibition formats rarely allow.

Since taking over its curatorship, Guillermo García Pérez has quietly transformed the EES into one of the most forward-thinking sonic spaces in Latin America. His curatorial approach is grounded in a sharp and timely critique: “We are currently in a moment where the avant-garde - as a guiding concept in the musical field - does not necessarily produce the most relevant works. Framing that search through a rigid scheme of delay-versus-progress is no longer effective if one seeks to explore works with political and historical significance.”

Rather than chase novelty for its own sake, García Pérez has opened the chamber to a different kind of sonic experimentation that operates at the intersection of politics, memory, and code - a “tension of fields.” Under his direction, the EES has hosted artists like Alva Noto, Laurie Spiegel, and Nicolás Jaar, each of whom explores sound as a method of historical reactivation. Jaar’s Radio Piedras, for instance, premiered an entirely new body of research that layered field recordings from mineral extraction zones in Latin America into a ghostly transmission about ecology and disappearance. The work was paired with a live concert that drew over 7,000 people to UNAM’s courtyard. Students stood in the fountain just to hear it. Spiegel’s algorithmic compositions moved through the space like digital folklore. Alva Noto’s signal geometries transformed planetary data into something emotional and strangely tactile.

These exhibitions often extend beyond the walls of the chamber. They become full events with concerts, lectures, and open discussions that recast the museum not as a container for meaning but as a site for inquiry. The question is not only what we hear but how we listen. And more urgently, who gets to make sound in the first place.

That same ethos animates Saturn Spectrums, the latest commission at the EES by artist Leslie García. In this 45-minute sound installation, García summons the spirit of Sun Ra, blending archival fragments with AI-assisted processing and modular synthesis. Rehearsal hiss, static, and ambient room tone are woven together with movements from García’s own phone. These gestures act as portals, linking past and future through noise. The result is spectral and unstable. Time folds in on itself. Sun Ra’s voice flickers as if hovering in unfinished transmission.

Saturn Spectrums refuses historical resolution. It allows decay to remain audible and turns glitches into connective threads. The archive is no longer a memory bank but a feedback loop. It lives through interference. It resists clarity.

It’s this feedback loop that defines the current moment at MUAC’s sound chamber. In an era where many museums are rebranding their collections and narratives, the EES takes a different approach. It asks what stories live inside the distortion. What can be learned by listening to what was meant to be erased. And what new sonic languages become possible when the signal is left unpolished.

Saturn Spectrums will loop through September, but its resonance is not bound to the room. In García’s work, and throughout García Pérez’s curatorial direction, the archive does not sit still. It flickers. It mutates. It breaks. And from that rupture, something begins to sound.

The politics and poetics of aguas frescas

by Ambika Subra.

At markets, fondas, and sunlit plazas, glass vitroleras cluster together, their bellies filled with horchata, jamaica, tamarindo - each sweating under the weight of the day. Inside, a long-handled ladle stirs slowly, ready to be dipped and poured into waiting plastic cups. One ladle. Many hands. These aren’t just beverages - they’re rituals of circulation: sweet, spiced, and hydrating, but also quietly collective. To drink is to join a shared rhythm. Aguas frescas carry not only flavor, but memory, labor, and the social codes of everyday life.

At this year’s TONO Festival, artist and fashion designer Bárbara Sánchez-Kane transformed this gesture into a durational performance of time, sound, and community. Founded by curator Samantha Ozer, TONO is a nomadic festival of time-based media that connects international artists with Mexico’s contemporary art scene across unconventional venues. In its third edition, Aguas Frescas unfolded over two days in the courtyard of Museo Anahuacalli, proposing a new kind of “poetry fountain” - where bodies, liquids, and instruments formed a mutable, sonic ecology. Against Diego Rivera’s basalt temple of pre-Columbian artifacts, Sánchez-Kane offered horchata as both metaphor and medium.

by Ambika Subra.

At markets, fondas, and sunlit plazas, glass vitroleras cluster together, their bellies filled with horchata, jamaica, tamarindo - each sweating under the weight of the day. Inside, a long-handled ladle stirs slowly, ready to be dipped and poured into waiting plastic cups. One ladle. Many hands. These aren’t just beverages - they’re rituals of circulation: sweet, spiced, and hydrating, but also quietly collective. To drink is to join a shared rhythm. Aguas frescas carry not only flavor, but memory, labor, and the social codes of everyday life.

At this year’s TONO Festival, artist and fashion designer Bárbara Sánchez-Kane transformed this gesture into a durational performance of time, sound, and community. Founded by curator Samantha Ozer, TONO is a nomadic festival of time-based media that connects international artists with Mexico’s contemporary art scene across unconventional venues. In its third edition, Aguas Frescas unfolded over two days in the courtyard of Museo Anahuacalli, proposing a new kind of “poetry fountain” - where bodies, liquids, and instruments formed a mutable, sonic ecology. Against Diego Rivera’s basalt temple of pre-Columbian artifacts, Sánchez-Kane offered horchata as both metaphor and medium.

The performance space resembled a clock. A custom off-white circular carpet marked the face, and twelve classic No. 10 chairs from Sillas Malinche stood in for numerals. Half were altered, their backrests replaced with tuned brass pipes, forming a percussive score. On six of them sat vitroleras of horchata. Inside each, a metal ladle spun, striking the pipes in a soft, liquid metronome.

Like the drinks it honors, Aguas Frescas was a blend of forms - performance, poetry, choreography, installation, and sound - stirred together across two afternoons. Day one featured Ariane Pellicer, performing a monologue by Ximena Escalante, alongside poetry collective Diles que no me maten. Day two brought Luisa Almaguer, Susana Vargas, Luis Felipe Fabre, Abraham Cruzvillegas, and composer Dario AFB (Darío Acuña Fuentes-Beraín). Dario’s sprinting circuit around the vitroleras built to a sonic crescendo, a symphonic finale of musical chairs.

At the center of it all was a shared drink. The simple act of dipping from the same jar of horchata became a quiet choreography of mutuality, echoing the performance’s structure. Just as audiences drew from a common vessel, Sánchez-Kane gathered an extended circle of collaborators to build the piece together. This wasn’t authorship but co-composition - a shared table, a living archive, a sonic ecology born through relation. It pulsed with the kind of togetherness that resists spectacle: generous, open, and held.

Throughout, Aguas Frescas reframed its namesake not as a beverage, but as a liquid commons. One rooted in gendered labor, domestic ritual, and social intimacy, passed across generations and sold at the margins of formality. The piece didn’t fetishize tradition. It made it vibrate - sonically, symbolically, materially. Even the sculptural details spoke in metaphor. Bent ladles echoed Sánchez-Kane’s signature motif of splayed, stilettoed legs, gesturing to queered, feminized, and often euphemized forms of care. In fact, “aguas frescas” is slang for orgy, a nod to its sensuality, multiplicity, and fleeting, messy mix.

Co-produced with MUDAM in Luxembourg, where it will travel this fall, Aguas Frescas isn’t truly exportable. Its strength lies in its rootedness - in sound shaped by sediment, in collaborators’ breath and tempo, in the durational patience of cooled heat. At Museo Anahuacalli, Sánchez-Kane’s performance didn’t elevate agua fresca. She reminded us it already holds meaning: archive, altar, and offering - if we pay attention to how it stirs.

Diego Vega Solorza: rewriting the language of dance

by Ambika Subra.

If you walk past a Mexico City park on a Saturday morning, you’ll likely see couples twirling to cumbia and salsa, their feet moving to rhythms passed down through generations. Movement is woven into the city’s fabric, a language of joy, spontaneity, and connection. But choreographer Diego Vega Solorza is not interested in dancing through time - he is interested in slowing it down and forcing us to sit inside its weight. His work does not unfold in bursts of rhythm but in suspension, where every gesture lingers, where movement becomes a living archive.

Vega Solorza is reshaping Mexican contemporary dance, rejecting the institutional validation that has long defined it. In a country where dance is often tied to folkloric tradition, he carves out a third space - one that refuses Eurocentric virtuosity and treats movement as a form of writing. His performances do not chase spectacle but command attention through stillness, through contrast, through the radical act of taking up time and space.

His latest work, Canto de Agua, presented at Galería LLANO in collaboration with Don Julio, embodies this philosophy. The performance is not just about water; it is a confrontation with how it is controlled, extracted, and fought over. The dancers, immersed in Rafael Durand’s live score and framed by Fernanda Caballero’s painted backdrop, move at an almost impossible pace—slow, deliberate, and fluid, as if suspended in water itself. Their movements demand patience, breaking the expectation that dance must entertain through speed. Canto de Agua transforms dance into a political act, where the body mirrors the fragility, resilience, and exploitation of natural forces.

Vega Solorza’s work flows between the political and the spiritual. Destellos de Luz, his previous collaboration with composer Dario afb, explores this balance through two opposing dancers in dialogue. One is soft and playful, the other sharp and assertive. They do not seek to merge but witness and admire each other’s differences, creating a tension that is as intimate as it is unpredictable. When they do align, the moment is rare and electric, dissolving as quickly as it forms. Their separation is just as powerful as their unity, turning the performance into a meditation on trust, distance, and the evolution of duality in space.

Vega Solorza’s work rejects the rigid hierarchies of classical dance, choosing instead to work with performers of all body types, identities, and backgrounds. His choreography does not rely on formal technique but on how people carry weight, how they inhabit space, how they move through a world that often demands they shrink themselves. He does not see dance as something to be perfected but as something to be written, rewritten, and preserved through repetition and memory.

"Nothing in my work is accidental. There are chronometers and counts, but there is no script," he explains.

Vega Solorza is building a new framework for contemporary dance, one that thrives outside the canon in Mexico City’s independent art and performance scenes. By expanding dance into visual art, music, and radical social and spiritual critique, Vega Solorza is not just shifting how dance is performed - he is reshaping how we experience time, movement, and human connection. His work demands patience. It demands attention. And in a world that is constantly moving faster, it reminds us of the power in slowing down, in witnessing, in waiting.

Mabe Fratti and the new sonic vanguard

by Ambika Subra.

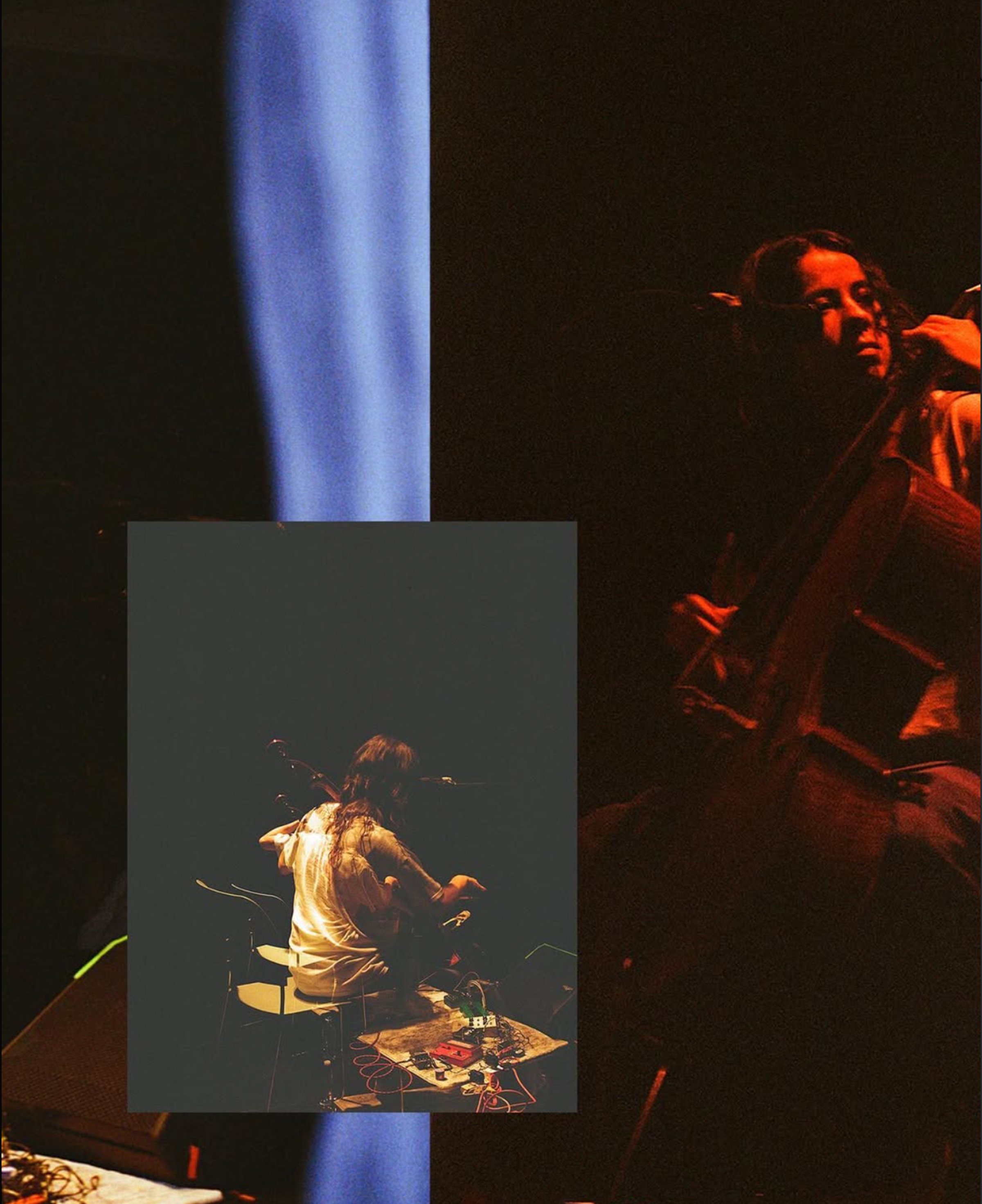

Amidst the horizontal vertigo of Zona Maco, where Mexico City’s galleries and restaurants overflow with collectors and influencers, something unexpected happened underground. Experimental cellists Mabe Fratti and Lucy Railton performed for a packed crowd of young Mexicans in the basement of the Jean Paul Gaultier showroom. Far removed from the spectacle of art commerce and spectacle, the cellists cut through the noise—an urgent exchange that redefined the cello’s role as a vessel for reinvention.

Mabe Fratti, Guatemalan-born and Mexico City-based, has been reshaping Mexico’s sonic landscape for the last decade. Her work blends composition and improvisation, intertwining the cello’s deep resonance with voice (in English and Spanish), electronic sounds, and unconventional plucking techniques. Once bound to orchestras and academia, Fratti reclaims the cello in experimental spaces, drawing full crowds and defying classical constraints. Her fluid, immersive approach expands the instrument’s vocabulary beyond its traditional lineage, much like Arthur Russell or Joanna Newsom.

Kuboraum-Innerraum and Tono Festival orchestrated this performance of Fratti and Railton—a rare convergence in the chaos of art week. Its salience was in its sonic alchemy—where classical instrumentation became a living, evolving force within Mexico’s underground. Here, the cello wasn’t an emblem of European high culture but a connective vessel of cross-border existence. Fratti and Railton didn’t just challenge tradition; they reframed it entirely for our contemporary. The music, swelling and unraveling in unpredictable waves, mirrored the cultural tensions outside—where Mexico City’s cosmopolitan sheen often masks a local underground scene pulsing with subversion.

This isn’t merely a stylistic evolution; it’s a philosophical shift reflected in Mexico City’s multicultural landscape. The embrace of classical instruments in the experimental scene speaks to a broader movement of young Mexicans and the artists settling in Mexico from abroad—resisting colonial baggage and establishing a third culture that does not abandon the past.

Mexico City’s artistic landscape thrives on inherited forms and contemporary reimaginings. As globalization accelerates cultural exchange, young artists are transforming these influences into something distinctly their own. For Fratti, this means erasing the line between performer and instrument, embracing her Guatemalan birth and her Mexican identity, and allowing voice, electronics, and tactile playing to merge into something raw and unfiltered. Her collaborations—whether in the haunting textures of Titanic, her project with Héctor Tosta, or the stark intimacy of her 2022 solo album Se Ve Desde Aquí—defy categorization.

“If I don’t know who I can be, then I am my feeling,” Fratti declares in the opening track of Vidrio, her collaborative album with Tosta (also known as I La Católica). Released under the moniker Titanic, Vidrio was one of three albums Fratti released in 2023, a testament to her restless creative energy and widespread resonance. Whether in solo work or collaborations, her music is rooted in transformation—of sound, of self, of the structures that define musical expression.

Here, the underground’s adoption of classical techniques isn’t nostalgia; it’s about reclaiming sound as something fluid, immediate, and unbound by expectation. It is the soundtrack of young creatives redefining the landscape in Mexico today. The cello, in the hands of Mabe Fratti, is neither an artifact nor a novelty, but a force—urgent, alive, and attuned to the city’s evolving pulse.

What lies beneath: the living archives of Lorena Mal

by Ambika Subra.

Unearthing the hidden narratives beneath our feet, Mexican artist Lorena Mal is revealing the deep entanglements between land and power. She is an excavator—not only of the earth’s soil and trees, but of the knowledge systems, political structures, and forgotten narratives embedded within it. Working across sculpture, performance, and archival intervention, Mal dismantles the illusion of landscape as a neutral backdrop. Instead, she exposes it as a charged site of conflict, migration, and resilience, shaped by forces both geological and geopolitical. One of the most exciting voices in contemporary Mexican art, her recent works at the XV Bienal FEMSA and Museo Jumex have cemented her place as a radical force in rethinking our experiences of landscape.

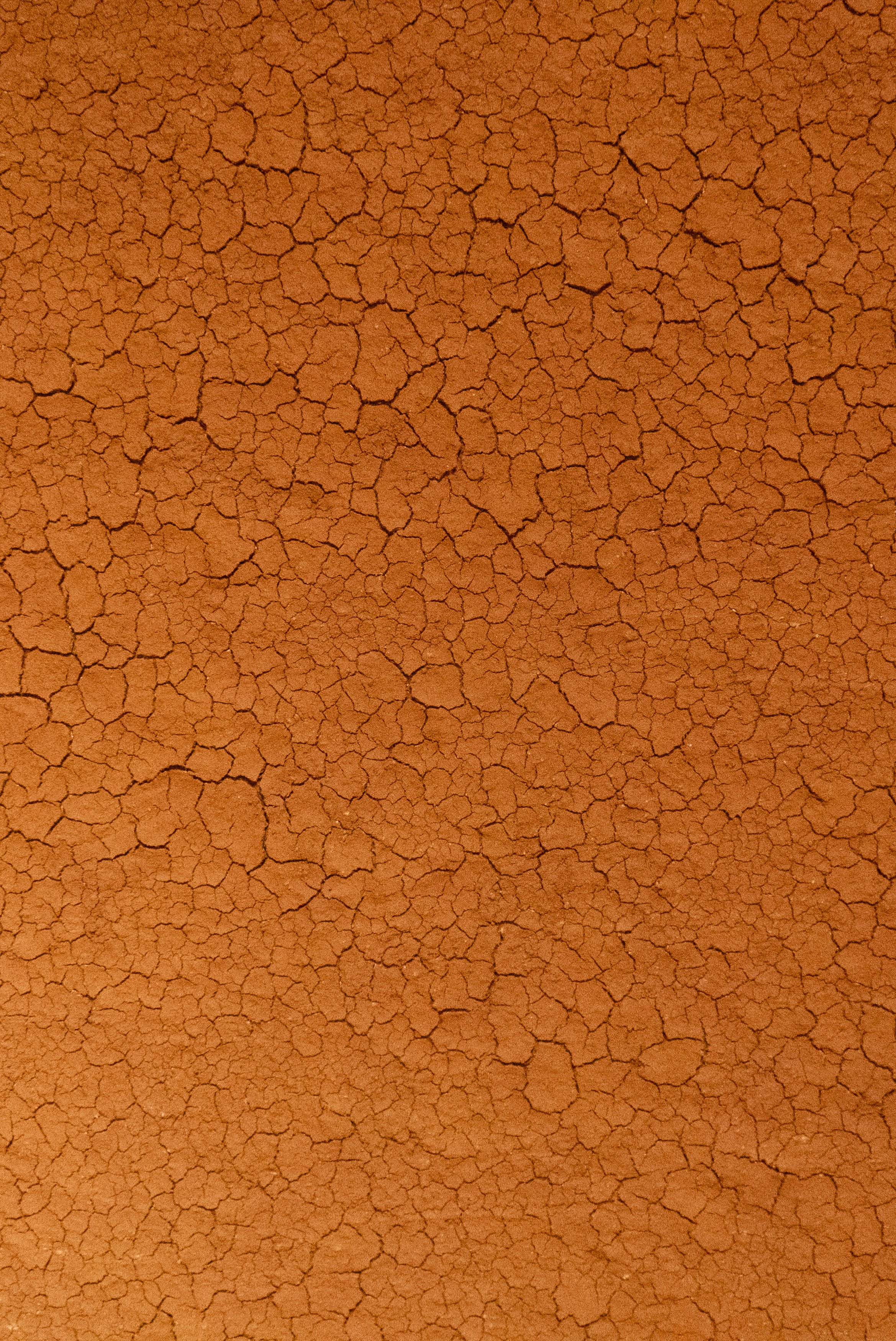

Mal refuses to see land as separate from history. In Restregarnos Tierra en los Ojos, an installation commissioned for the XV Bienal FEMSA, she created an archive of occupation and displacement by covering the space’s surfaces with soil—a raw, living material applied in a fermented state, allowing microbial life and air to bind it into a clay that naturally cracked and shifted over the four months of the exhibition. Sourced from the Bajío, the soil bore the region’s long past of floods and droughts, colonial mining extraction, and environmental destruction. Who has the right to a land? Who determines its fate? Mal’s intervention blurred the lines between architecture and archaeology, embedding the region’s instability directly into the walls of the exhibition. The soil itself became testimony—not just a metaphor, but an active record of conflict, survival, and resistance.

Beyond the visible, Mal’s work listens. In Largo Aliento, performed at Museo Jumex this past year, she translated tree rings into sonic compositions, using instruments made from those trees as a vehicle for a deep, resonant breath. Just as the soil preserves and reveals the memory of land through its raw materiality, Largo Aliento treats breath as a conduit for memory, where tree rings vocalize their silent histories. These rings, like layers of sediment, hold the imprints of environmental upheavals—fires, droughts, cycles of violence and renewal. By playing their breath, Mal does not impose a structure onto their histories but coaxes out their latent recollections, turning them into sound. Her instruments do not adhere to tempered scales or fixed notation, but instead respond to human interaction. This relationship resists linear time in favor of something more fluid and horizontal, creating a resonance that blurs the boundary between past and present. Both earth and breath become modes of listening—fragile yet persistent archives of what landscapes remember.

History is not confined to human narratives alone. At its core, Lorena Mal’s work is about destabilization—of narrative, of power, of our very understanding of place. She is not interested in transformation as a fixed act but in how landscape holds and reveals its own records through its raw architecture. Mal excavates how land bears witness to colonial displacements, migrations both human and botanical, and the erasure embedded in plantation histories. By blending materials across geographies, carving new sonic pathways through time, and forcing us to confront what lies beneath our feet, Mal reframes the land as an active force—one that remembers, resists, and refuses erasure. Her practice is not simply an exploration of landscape; it is a reconfiguration of how we engage with the world itself.