From London, MexCC charts a global course for Mexico

by Andrew Law.

There’s something energising about a well-calibrated relaunch — especially when the setting is a warm London terrace on a summer’s evening, and the ambition on display is global. This week, the Mexican Chamber of Commerce in Great Britain (MexCC), which I’m happy to note The Mexico Brief is officially partnered with, reintroduced itself not just with new branding, but with a revitalised vision: Mexico, connected to the world through London.

Originally founded in 2011, the Chamber has long served as a bridge for trade and culture. But as its Honorary Chairman Yves Hayaux du Tilly noted during the relaunch event at The In & Out Club, the new MexCC operates as more than a network: “We are building a movement… giving Mexico a stronger voice, a strategic presence, and a platform to lead globally from London.”

It’s an audacious goal, sure, but not an unfounded one. The new model, built on pillars of investment, trade, culture, and technology, frames Mexico not as a peripheral player, but as a central force in a world increasingly defined by shifting alliances and cross-continental innovation.

There’s structure to back the rhetoric. A new governance framework connects senior advisors with young professionals. Meanwhile, services like MexConnect and MexTradeHub offer members the chance to network, create market traction and acquire strategic intelligence.

The Chamber is leaning into London’s role as a global finance and innovation hub, positioning Mexican companies to scale with European capital and international partnerships. As María Ariza, CEO of BIVA, put it, “Connecting Mexican companies with UK and European capital is essential.”

There has always been huge opportunity to deepen the UK and Mexico’s commercial and cultural exchange. Now there’s a credible forum to do just that. Gabriel Anguiano, MexCC’s Chairman, put it in succinct terms: “What emerges now is not just a relaunch -- but a reinvention.”

One to watch. One to join.

Mexico City’s MUAC is a hub for sonic experimentation

by Ambika Subra.

Mexico City has more museums than any other city in the world. Whether conceptual or commodified, contemporary art can be found in every colonia. But the seed of contemporary art lies in its debate, which is why one of the city’s most vital cultural gems sits not in a gallery district or a downtown corridor, but on the campus of UNAM. What sets El Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) apart in the Mexican museum landscape is its Espacio de Experimentación Sonora (EES), a room designed exclusively for experimental music. It offers more than a space for sound. It creates the conditions for deep listening. Its architecture invites not spectacle but study. It is a purpose-made environment for sonic research, where artists stretch time, distort history, and activate archives in ways that traditional exhibition formats rarely allow.

Since taking over its curatorship, Guillermo García Pérez has quietly transformed the EES into one of the most forward-thinking sonic spaces in Latin America. His curatorial approach is grounded in a sharp and timely critique: “We are currently in a moment where the avant-garde - as a guiding concept in the musical field - does not necessarily produce the most relevant works. Framing that search through a rigid scheme of delay-versus-progress is no longer effective if one seeks to explore works with political and historical significance.”

Rather than chase novelty for its own sake, García Pérez has opened the chamber to a different kind of sonic experimentation that operates at the intersection of politics, memory, and code - a “tension of fields.” Under his direction, the EES has hosted artists like Alva Noto, Laurie Spiegel, and Nicolás Jaar, each of whom explores sound as a method of historical reactivation. Jaar’s Radio Piedras, for instance, premiered an entirely new body of research that layered field recordings from mineral extraction zones in Latin America into a ghostly transmission about ecology and disappearance. The work was paired with a live concert that drew over 7,000 people to UNAM’s courtyard. Students stood in the fountain just to hear it. Spiegel’s algorithmic compositions moved through the space like digital folklore. Alva Noto’s signal geometries transformed planetary data into something emotional and strangely tactile.

These exhibitions often extend beyond the walls of the chamber. They become full events with concerts, lectures, and open discussions that recast the museum not as a container for meaning but as a site for inquiry. The question is not only what we hear but how we listen. And more urgently, who gets to make sound in the first place.

That same ethos animates Saturn Spectrums, the latest commission at the EES by artist Leslie García. In this 45-minute sound installation, García summons the spirit of Sun Ra, blending archival fragments with AI-assisted processing and modular synthesis. Rehearsal hiss, static, and ambient room tone are woven together with movements from García’s own phone. These gestures act as portals, linking past and future through noise. The result is spectral and unstable. Time folds in on itself. Sun Ra’s voice flickers as if hovering in unfinished transmission.

Saturn Spectrums refuses historical resolution. It allows decay to remain audible and turns glitches into connective threads. The archive is no longer a memory bank but a feedback loop. It lives through interference. It resists clarity.

It’s this feedback loop that defines the current moment at MUAC’s sound chamber. In an era where many museums are rebranding their collections and narratives, the EES takes a different approach. It asks what stories live inside the distortion. What can be learned by listening to what was meant to be erased. And what new sonic languages become possible when the signal is left unpolished.

Saturn Spectrums will loop through September, but its resonance is not bound to the room. In García’s work, and throughout García Pérez’s curatorial direction, the archive does not sit still. It flickers. It mutates. It breaks. And from that rupture, something begins to sound.

The politics and poetics of aguas frescas

by Ambika Subra.

At markets, fondas, and sunlit plazas, glass vitroleras cluster together, their bellies filled with horchata, jamaica, tamarindo - each sweating under the weight of the day. Inside, a long-handled ladle stirs slowly, ready to be dipped and poured into waiting plastic cups. One ladle. Many hands. These aren’t just beverages - they’re rituals of circulation: sweet, spiced, and hydrating, but also quietly collective. To drink is to join a shared rhythm. Aguas frescas carry not only flavor, but memory, labor, and the social codes of everyday life.

At this year’s TONO Festival, artist and fashion designer Bárbara Sánchez-Kane transformed this gesture into a durational performance of time, sound, and community. Founded by curator Samantha Ozer, TONO is a nomadic festival of time-based media that connects international artists with Mexico’s contemporary art scene across unconventional venues. In its third edition, Aguas Frescas unfolded over two days in the courtyard of Museo Anahuacalli, proposing a new kind of “poetry fountain” - where bodies, liquids, and instruments formed a mutable, sonic ecology. Against Diego Rivera’s basalt temple of pre-Columbian artifacts, Sánchez-Kane offered horchata as both metaphor and medium.

by Ambika Subra.

At markets, fondas, and sunlit plazas, glass vitroleras cluster together, their bellies filled with horchata, jamaica, tamarindo - each sweating under the weight of the day. Inside, a long-handled ladle stirs slowly, ready to be dipped and poured into waiting plastic cups. One ladle. Many hands. These aren’t just beverages - they’re rituals of circulation: sweet, spiced, and hydrating, but also quietly collective. To drink is to join a shared rhythm. Aguas frescas carry not only flavor, but memory, labor, and the social codes of everyday life.

At this year’s TONO Festival, artist and fashion designer Bárbara Sánchez-Kane transformed this gesture into a durational performance of time, sound, and community. Founded by curator Samantha Ozer, TONO is a nomadic festival of time-based media that connects international artists with Mexico’s contemporary art scene across unconventional venues. In its third edition, Aguas Frescas unfolded over two days in the courtyard of Museo Anahuacalli, proposing a new kind of “poetry fountain” - where bodies, liquids, and instruments formed a mutable, sonic ecology. Against Diego Rivera’s basalt temple of pre-Columbian artifacts, Sánchez-Kane offered horchata as both metaphor and medium.

The performance space resembled a clock. A custom off-white circular carpet marked the face, and twelve classic No. 10 chairs from Sillas Malinche stood in for numerals. Half were altered, their backrests replaced with tuned brass pipes, forming a percussive score. On six of them sat vitroleras of horchata. Inside each, a metal ladle spun, striking the pipes in a soft, liquid metronome.

Like the drinks it honors, Aguas Frescas was a blend of forms - performance, poetry, choreography, installation, and sound - stirred together across two afternoons. Day one featured Ariane Pellicer, performing a monologue by Ximena Escalante, alongside poetry collective Diles que no me maten. Day two brought Luisa Almaguer, Susana Vargas, Luis Felipe Fabre, Abraham Cruzvillegas, and composer Dario AFB (Darío Acuña Fuentes-Beraín). Dario’s sprinting circuit around the vitroleras built to a sonic crescendo, a symphonic finale of musical chairs.

At the center of it all was a shared drink. The simple act of dipping from the same jar of horchata became a quiet choreography of mutuality, echoing the performance’s structure. Just as audiences drew from a common vessel, Sánchez-Kane gathered an extended circle of collaborators to build the piece together. This wasn’t authorship but co-composition - a shared table, a living archive, a sonic ecology born through relation. It pulsed with the kind of togetherness that resists spectacle: generous, open, and held.

Throughout, Aguas Frescas reframed its namesake not as a beverage, but as a liquid commons. One rooted in gendered labor, domestic ritual, and social intimacy, passed across generations and sold at the margins of formality. The piece didn’t fetishize tradition. It made it vibrate - sonically, symbolically, materially. Even the sculptural details spoke in metaphor. Bent ladles echoed Sánchez-Kane’s signature motif of splayed, stilettoed legs, gesturing to queered, feminized, and often euphemized forms of care. In fact, “aguas frescas” is slang for orgy, a nod to its sensuality, multiplicity, and fleeting, messy mix.

Co-produced with MUDAM in Luxembourg, where it will travel this fall, Aguas Frescas isn’t truly exportable. Its strength lies in its rootedness - in sound shaped by sediment, in collaborators’ breath and tempo, in the durational patience of cooled heat. At Museo Anahuacalli, Sánchez-Kane’s performance didn’t elevate agua fresca. She reminded us it already holds meaning: archive, altar, and offering - if we pay attention to how it stirs.

‘Roma’ producer pushes craft, artistry amid Mexico’s creative boom

by Ambika Subra.

Mexico’s film industry has long been a wellspring of creativity, producing visionary filmmakers while remaining just outside the global spotlight. But some sense the center may be shifting. In February, Netflix announced a $1 billion commitment to Mexican productions over the next five years, raising the stakes and highlighting Mexico as a key figure in the future of global cinema. At Pimienta Films - the Oscar-winning production company behind Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Tatiana Huezo’s Noche de Fuego - that future isn’t simply about making more movies. It’s about making better ones, and building the artistic ecosystems that can carry Mexican cinema into its next era.

Few are better positioned to lead this shift than Nicolás Celis, Pimienta’s founder. Celis has helped define the shape of contemporary Mexican cinema. For him, the current moment is as urgent as it is expansive.

"Mexico is in a very vibrant position right now," Celis tells me. Production is at an all-time high, fueled by fiscal incentives and the influx of streamers setting up bases across Mexico City. "It’s the gateway between this new streaming economy and the rest of Latin America." Major studios are investing heavily - not just in infrastructure, but in securing a foothold in a market that’s growing rapidly in both content consumption and creative output.

by Ambika Subra.

Mexico’s film industry has long been a wellspring of creativity, producing visionary filmmakers while remaining just outside the global spotlight. But some sense the center may be shifting. In February, Netflix announced a $1 billion commitment to Mexican productions over the next five years, raising the stakes and highlighting Mexico as a key figure in the future of global cinema. At Pimienta Films - the Oscar-winning production company behind Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Tatiana Huezo’s Noche de Fuego - that future isn’t simply about making more movies. It’s about making better ones, and building the artistic ecosystems that can carry Mexican cinema into its next era.

Few are better positioned to lead this shift than Nicolás Celis, Pimienta’s founder. Celis has helped define the shape of contemporary Mexican cinema. For him, the current moment is as urgent as it is expansive.

"Mexico is in a very vibrant position right now," Celis tells me. Production is at an all-time high, fueled by fiscal incentives and the influx of streamers setting up bases across Mexico City. "It’s the gateway between this new streaming economy and the rest of Latin America." Major studios are investing heavily - not just in infrastructure, but in securing a foothold in a market that’s growing rapidly in both content consumption and creative output.

But while production services for international films, TV shows, and advertisements are booming, Celis sees a deeper challenge for homegrown cinema. "Ten years ago, there was a huge appetite for Mexican films everywhere," he reflects. "Now, that hunger has shifted to other geographies." The result is a feeling of stasis, a repetition of familiar subjects and forms without a true update that captures the complexity and vibrancy of contemporary Mexico. “Audiences are eager for freshness,” he insists. “An evolution.”

Netflix’s $1 billion investment, Celis believes, won't automatically deliver that. “The money isn’t new," he says. "What’s new is the recognition of just how crucial the Mexican market is.” But quantity alone isn’t the answer. For a company like Pimienta, there’s a different mandate. "It’s not about making more. It’s about raising the level at which we create."

At a time when the industry could easily chase volume, Pimienta is setting a different course: one rooted in craftsmanship, depth, and long-term vision. In a streaming era that favors speed, Celis is holding fast to something rarer. "Films are cultural products, not consumer products," he says. "If you don’t connect with an audience, what’s the point?"

It’s a philosophy that runs deeper than any single project, aiming to rebuild the foundations that sustain great filmmaking. “We have amazing stories and grateful makers,” Celis says, “but we also need to connect the expertise of distributors, exhibitors, and producers. We have to expand the dialogue.” Mexico’s creative industries must grow not just outward but inward - fortifying the artistic community that makes lasting cinema possible.

One of Pimienta’s upcoming projects, Insectario, embodies this vision. Directed by renowned stop-motion artist Sofía Carrillo - who worked on Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio - and co-written with screenwriter Mónica Revilla, Insectario isn’t just a film. It’s a showcase of Mexican artistry at every level: animators, writers, designers, and technicians. A stop-motion feature made in Mexico, by Mexican artists, for a global audience. "It’s not enough to make a beautiful movie," Celis says. "We want to build careers, build industries, show what Mexican craft can do."

This is part of a broader shift in Pimienta’s approach, forged in the aftermath of Roma. "After Roma, I understood it’s not only about making a movie," Celis reflects. "It’s about how you position that movie so it can survive the passing of time."

For Pimienta, the future of Mexican cinema doesn’t lie in chasing trends or maximizing output. It lies in doubling down on excellence - making work that connects, challenges, and endures. “Mexico is setting examples for Latin America,” Celis says. “And the only way to guarantee stability is by continuing to make great films, great stories.”

In a moment when all eyes are on Mexico, Pimienta isn’t content to simply ride the wave. They’re shaping the horizon: building an industry where artistry, craft, and connection aren’t afterthoughts, but the foundation.

After Netflix’s billion, the real work begins. And as Pimienta’s vision takes hold, the future of Mexican cinema could be even more extraordinary than its past.

“Horizontal vertigo” and the architecture of Pato

by Ambika Subra.

Juan Villoro now famously referred to Mexico City as a “horizontal vertigo” - a place that unfolds not upward but outward, a labyrinth of nonlinear, magical chaos. To live here is to get lost and found in equal measure. It’s a city where a last-minute lunch can shift your day, where you might follow a stranger into a new neighborhood and come out with a lifelong friend, or find yourself questioning everything because of a particular alleyway.

It was in this horizontal vertigo that I found myself having dinner with a close friend and renowned architect: Patricio “Pato” Galindo Chain.

To understand Pato's architecture is to understand how he inhabits his city. His work - spanning from the boutique Hotel Dama in Mexico City to the retreat Mi Cielo in Valle de Bravo - rarely announces itself with grandiosity. Instead, it collaborates with history, with time, with those who move through it. His motto: “Architecture is precisely the construction of a space by inhabiting it.”

by Ambika Subra.

Juan Villoro now famously referred to Mexico City as a “horizontal vertigo” - a place that unfolds not upward but outward, a labyrinth of nonlinear, magical chaos. To live here is to get lost and found in equal measure. It’s a city where a last-minute lunch can shift your day, where you might follow a stranger into a new neighborhood and come out with a lifelong friend, or find yourself questioning everything because of a particular alleyway.

It was in this horizontal vertigo that I found myself having dinner with a close friend and renowned architect: Patricio “Pato” Galindo Chain.

To understand Pato's architecture is to understand how he inhabits his city. His work - spanning from the boutique Hotel Dama in Mexico City to the retreat Mi Cielo in Valle de Bravo - rarely announces itself with grandiosity. Instead, it collaborates with history, with time, with those who move through it. His motto: “Architecture is precisely the construction of a space by inhabiting it.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in Nogal 59, his residence in Santa María la Ribera. To describe its architecture is to describe the way Pato tells stories, lives in loops, and designs with a sensitivity to rhythm - visual, social, and temporal.

Santa María la Ribera is one of Mexico City’s oldest neighborhoods, a blend of French mansions and DIY repairs, where chaos isn’t an inconvenience but a pattern. On Pato’s street, Calle Nogal, there are no curated storefronts. Instead, rotating clusters of mechanics spill onto the sidewalks like shifting exhibits. Depending on the car parked out front - a cherry-red sedan, a deep green antique van—the light inside Nogal 59 shifts.

This is a feedback loop. Exterior becomes interior. Interior becomes story.

The house itself is a three-story structure designed for one person, but it never feels solitary. “The symphony of the street,” he says, “is a presence I share my space with. It's my timekeeper.” At 6:30am, the smell of burning wood from the tamale vendor cracks open the day. By 11:30pm, a pulsing techno beat signals the arrival of a vendor no one sees but everyone expects. These sounds don’t just mark time, but shape being.

There is rhythm, but never stasis. The vintage tiles, warm woods, and restored furnishings reflect a reverence for the past, but the home exists in fluid motion. It accepts contradiction - modern and antique, open and enclosed.

Sometimes, movement across space requires crossing boundaries: rooftops, windows, time. Pato once had to crawl through a neighbor’s roof to re-enter his own home after being locked out. Another time, a seismic alarm revealed a neighbor’s hidden menagerie - cats, birds, even possums. These moments aren’t exceptions, but extensions of the home itself. When walls become porous, stories seep through.

This porousness defines Nogal 59. Plants lean against gridded steel windows. A hallway stretches alongside glass, letting the light shift throughout the day. In a bedroom, a tree outside seems to crawl into the closet. The house doesn’t contain a story, but loops it. The street becomes the house. The house reflects the street. A home becomes a living document of place.

As Villoro might suggest, it’s not just horizontal - it’s vertiginous. Because in that outward sprawl, there’s also deep descent: into memory, collaboration, layered time. To describe Pato’s work is not to list achievements or styles, but to map a way of moving through the world. His architecture is built not just with materials, but with motion, atmosphere, and entanglement. It is an architecture of chaos. And Nogal 59, at the corner of Calle Nogal and everything else, is where the work starts living.

Editor’s Note: A fuller selection of Pato’s work can be viewed via his firm’s website, here.

Stitched in resistance: Montserrat Messeguer and the Norteña revolution

by Ambika Subra.

A resistance movement is sweeping through Mexico, stitched in deep brown leather, dusted with desert sand, and pulsing to the rhythms of Norteño cowboys - or rather, cowgirls. Once tied to rural identity, Norteño fashion is now stepping into the global spotlight, fueled by the meteoric rise of modern corrido music. Artists like Peso Pluma and Natanael Cano are carrying the sound of the North to international audiences, evolving the image of the modern vaquero. At the heart of this cultural shift stands Montserrat Messeguer, a designer transforming Norteño fashion from a regional aesthetic into a global statement of power, defiance, and female empowerment—a vehicle for the women’s revolutionary movement that is redefining Mexico’s cultural narrative.

For decades, cowboy culture was synonymous with masculinity, shaped by charros, ranchers, and corrido ballads that celebrated the rugged toughness of men. Today’s vaquero, however, is a sleek icon—boots polished, gold chains glinting, blending designer brands with ranchero influences. Corrido superstars have turned cowboy boots, massive belt buckles, and wide-brimmed hats into symbols of success, rewriting the tumbado aesthetic. Yet, the true revolution lies in women claiming this identity. Led by visionaries like Messeguer, they’re using fashion to challenge patriarchal norms and assert their place in this storied tradition.

Messeguer’s designs are at the forefront of this women’s revolutionary movement, empowering the modern Norteña to lead the charge. Her collections, worn by global icons like Dua Lipa and Emily Ratajkowski, reframe Norteño fashion as a platform for female strength and independence. The modern vaquera she envisions isn’t a background figure—she’s the protagonist, bold and unapologetic. This shift echoes broader changes in cowboy culture, where escaramuzas—Mexico’s fearless female equestrians—are gaining visibility, their elegance and athleticism earning admiration in the male-dominated world of rodeo. Messeguer’s charro-inspired silhouettes and resilient leather pieces honor these women, celebrating their power.

This Norteño resurgence reflects a global hunger for something raw and untamed in a digital, corporate-driven world. The cowboy symbolizes self-reliance and freedom. For women, this revival is resistance. Fashion becomes their vehicle to fight for visibility, challenging hierarchical structures that have sidelined them. Messeguer’s designs—leathers from traditional artisans, cuts echoing charro uniforms—tell this story of defiance, weaving the past into a future where women lead.

Raised between Northern Mexico and Mexico City’s creative scene, Messeguer fuses historical craftsmanship with modern tailoring, proving Norteño style is a living language of tradition and reinvention. Her work rewrites the cowboy narrative, centering women as revolutionary figures bridging past and future, rural roots and global stages.

As Norteño fashion ascends, the question is no longer whether it belongs in high fashion, but how far its influence will reach. Messeguer and her contemporaries are proving that the cowboy is not a museum artifact but a vibrant, evolving figure—especially in the form of a woman who embodies the spirit of resistance. In her hands, the Norteño aesthetic isn’t just surviving—it’s thriving. The boots are back, the hats are sharp, and the story of the North is being retold.

Only this time, it’s by the Norteñas, and the whole world is listening.

How Tampico’s alien embrace transformed fear and uncertainty into hopeful resilience

by Ambika Subra.

Forget Roswell - if extraterrestrials have landed anywhere, it’s Tampico.

A port city on Mexico’s Gulf Coast, Tampico has been shaped by invasion - Spanish conquest, French occupation, oil booms that lured American investors, and even colonies of raccoons that spread across the beaches after migrating from the destroyed Casuarinas forest. In the 2010s, the city faced a darker invasion, one that turned Tampico into both a war zone and a cautionary headline. Cartel violence swept through the area. Entire families disappeared overnight. Military trucks patrolled the streets. A city-wide curfew emptied plazas and shuttered local businesses.

In Mexico, the extranjero - foreigner, outsider, alien - has long been a symbol of conquest, uncertainty, and fear. For Tampiqueños, the unknown has never been distant or abstract. It has arrived in waves, seizing power, land, and lives. And yet, despite a history of violent invasion, Tampico has refused to surrender to fear. Instead, it has rewritten the meaning of the extranjero, embedding it into collective consciousness. And in this rewritten mythology, the outsider is not a force of destruction, but protection. The alien - quite literally, the green figure with a large head and a UFO - is the extranjero that defines the city, not as an invader, but as a silent guardian.

For over 60 years, many Tampiqueños have believed in Amupac, an underwater alien base 1.3 kilometers off Miramar Beach, shielding the city from natural disaster. While other regions along the Gulf Coast - Veracruz, Texas, Louisiana - have suffered catastrophic hurricanes, Tampico has remained untouched since 1966. The reason, according to locals, isn’t meteorological luck. It’s extraterrestrial intervention.

Journalist and ufologist Jaime Maussan, Mexico’s most famous alien investigator, traced the legend’s origins to an American tourist in the 1970s who claimed to have been abducted and taken to a submerged extraterrestrial city beneath the Gulf. Newspapers in Tampico and Ciudad Madero published the story as fact. Since then, with each hurricane that shifts course, belief in Amupac has only grown. Fishermen often report strange lights beneath the water. Radar interference remains unexplained. Unexplained objects hover over oil rigs. One local meteorologist interviewed by Vice News stressed there are several more terrestrial explanations for why a hurricane hasn’t hit Tampico since 1966. But many Tampiqueños remain convinced: something - or someone - is protecting them from true destruction.

Tampico’s aliens are not just a conspiracy theory or local legend. They are embedded in the city’s cultural fabric. Walk along the beaches, and you’ll see murals of UFOs, alien sculptures, and plush green companions sold at market stalls. Raccoons roam around a half-buried flying saucer on the beach. Every year, the city holds UFO conferences and a parade where residents dress as extraterrestrials, turning myth into collective history. Many make pilgrimages to Miramar Beach to meditate, hoping to connect with their unseen protectors.

The phenomenon has even led to structured research - most notably through la Asociación de Investigación Científica Ovni de Tamaulipas, an organization dedicated to studying UFO sightings and unexplained aerial phenomena in the region. Netflix is scouting the area for a documentary.

But the significance of this mythology isn’t aesthetic or for tourism. It’s about collective survival - a way to reclaim power in a place that has been shaped by forces beyond its control. Just as Tampico has endured colonial occupations and cartel wars, it has also found a way to turn the unknown - the fear of the extranjero - into something protective and hopeful.

The unknown is so often framed as a source of fear, but Tampico offers a rare counter-narrative: what we don’t understand can often protect us the most.

The existence of Amupac in Tampiqueños’ minds isn’t about scientific proof. It’s about something deeper - the way mythology gives people meaning, survival, and identity. Faith in these cosmic protectors has become a form of resilience. It is a way to reclaim control in a context where the unknown has often dictated the city’s fate. The belief in Amupac extends beyond aliens. It’s about the power to turn fear into protection, to transform uncertainty into faith.

And that’s the real power of Tampico’s aliens. Whether or not they exist is moot. Tampiqueños have made them real.

Diego Vega Solorza: rewriting the language of dance

by Ambika Subra.

If you walk past a Mexico City park on a Saturday morning, you’ll likely see couples twirling to cumbia and salsa, their feet moving to rhythms passed down through generations. Movement is woven into the city’s fabric, a language of joy, spontaneity, and connection. But choreographer Diego Vega Solorza is not interested in dancing through time - he is interested in slowing it down and forcing us to sit inside its weight. His work does not unfold in bursts of rhythm but in suspension, where every gesture lingers, where movement becomes a living archive.

Vega Solorza is reshaping Mexican contemporary dance, rejecting the institutional validation that has long defined it. In a country where dance is often tied to folkloric tradition, he carves out a third space - one that refuses Eurocentric virtuosity and treats movement as a form of writing. His performances do not chase spectacle but command attention through stillness, through contrast, through the radical act of taking up time and space.

His latest work, Canto de Agua, presented at Galería LLANO in collaboration with Don Julio, embodies this philosophy. The performance is not just about water; it is a confrontation with how it is controlled, extracted, and fought over. The dancers, immersed in Rafael Durand’s live score and framed by Fernanda Caballero’s painted backdrop, move at an almost impossible pace—slow, deliberate, and fluid, as if suspended in water itself. Their movements demand patience, breaking the expectation that dance must entertain through speed. Canto de Agua transforms dance into a political act, where the body mirrors the fragility, resilience, and exploitation of natural forces.

Vega Solorza’s work flows between the political and the spiritual. Destellos de Luz, his previous collaboration with composer Dario afb, explores this balance through two opposing dancers in dialogue. One is soft and playful, the other sharp and assertive. They do not seek to merge but witness and admire each other’s differences, creating a tension that is as intimate as it is unpredictable. When they do align, the moment is rare and electric, dissolving as quickly as it forms. Their separation is just as powerful as their unity, turning the performance into a meditation on trust, distance, and the evolution of duality in space.

Vega Solorza’s work rejects the rigid hierarchies of classical dance, choosing instead to work with performers of all body types, identities, and backgrounds. His choreography does not rely on formal technique but on how people carry weight, how they inhabit space, how they move through a world that often demands they shrink themselves. He does not see dance as something to be perfected but as something to be written, rewritten, and preserved through repetition and memory.

"Nothing in my work is accidental. There are chronometers and counts, but there is no script," he explains.

Vega Solorza is building a new framework for contemporary dance, one that thrives outside the canon in Mexico City’s independent art and performance scenes. By expanding dance into visual art, music, and radical social and spiritual critique, Vega Solorza is not just shifting how dance is performed - he is reshaping how we experience time, movement, and human connection. His work demands patience. It demands attention. And in a world that is constantly moving faster, it reminds us of the power in slowing down, in witnessing, in waiting.

Mabe Fratti and the new sonic vanguard

by Ambika Subra.

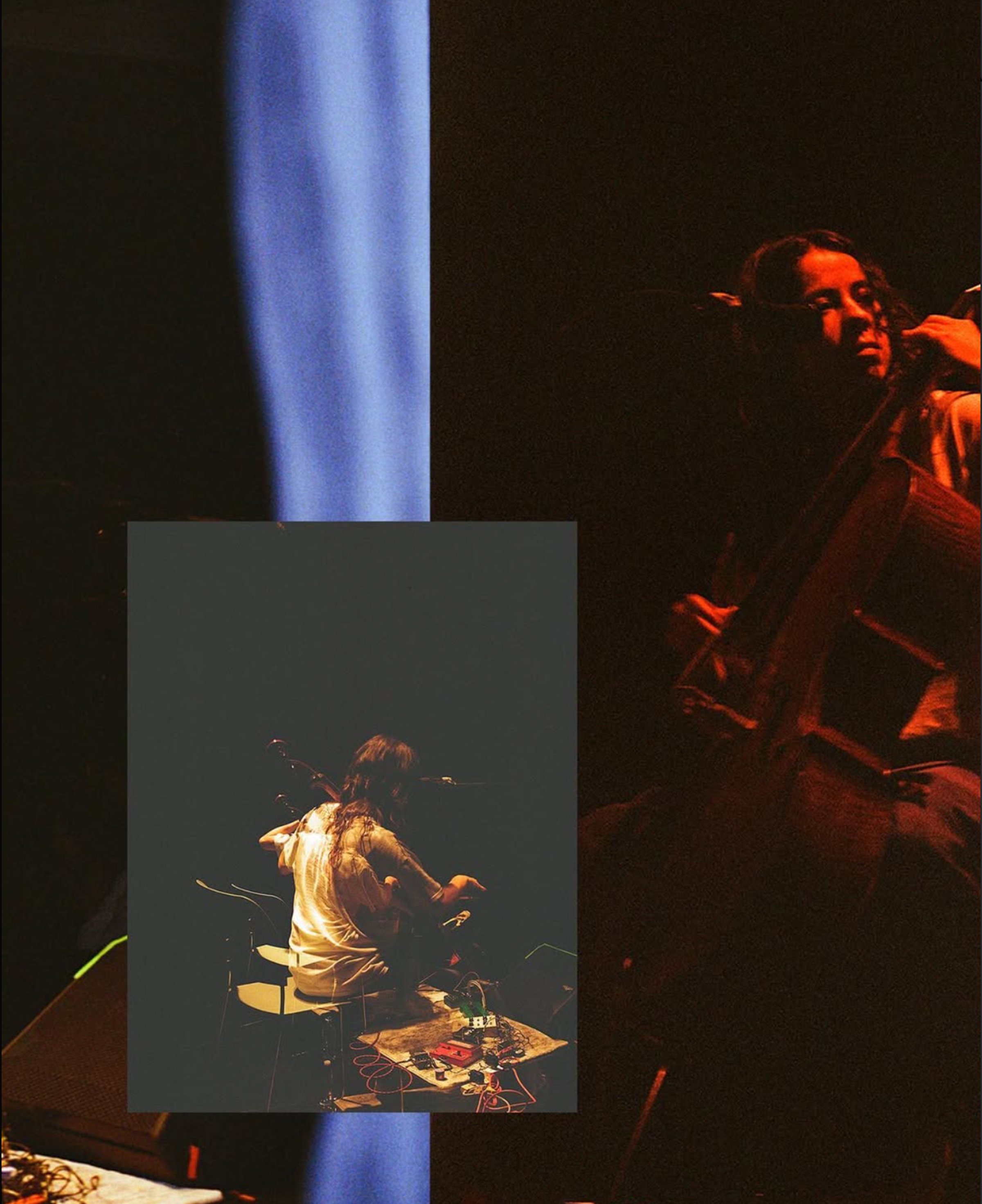

Amidst the horizontal vertigo of Zona Maco, where Mexico City’s galleries and restaurants overflow with collectors and influencers, something unexpected happened underground. Experimental cellists Mabe Fratti and Lucy Railton performed for a packed crowd of young Mexicans in the basement of the Jean Paul Gaultier showroom. Far removed from the spectacle of art commerce and spectacle, the cellists cut through the noise—an urgent exchange that redefined the cello’s role as a vessel for reinvention.

Mabe Fratti, Guatemalan-born and Mexico City-based, has been reshaping Mexico’s sonic landscape for the last decade. Her work blends composition and improvisation, intertwining the cello’s deep resonance with voice (in English and Spanish), electronic sounds, and unconventional plucking techniques. Once bound to orchestras and academia, Fratti reclaims the cello in experimental spaces, drawing full crowds and defying classical constraints. Her fluid, immersive approach expands the instrument’s vocabulary beyond its traditional lineage, much like Arthur Russell or Joanna Newsom.

Kuboraum-Innerraum and Tono Festival orchestrated this performance of Fratti and Railton—a rare convergence in the chaos of art week. Its salience was in its sonic alchemy—where classical instrumentation became a living, evolving force within Mexico’s underground. Here, the cello wasn’t an emblem of European high culture but a connective vessel of cross-border existence. Fratti and Railton didn’t just challenge tradition; they reframed it entirely for our contemporary. The music, swelling and unraveling in unpredictable waves, mirrored the cultural tensions outside—where Mexico City’s cosmopolitan sheen often masks a local underground scene pulsing with subversion.

This isn’t merely a stylistic evolution; it’s a philosophical shift reflected in Mexico City’s multicultural landscape. The embrace of classical instruments in the experimental scene speaks to a broader movement of young Mexicans and the artists settling in Mexico from abroad—resisting colonial baggage and establishing a third culture that does not abandon the past.

Mexico City’s artistic landscape thrives on inherited forms and contemporary reimaginings. As globalization accelerates cultural exchange, young artists are transforming these influences into something distinctly their own. For Fratti, this means erasing the line between performer and instrument, embracing her Guatemalan birth and her Mexican identity, and allowing voice, electronics, and tactile playing to merge into something raw and unfiltered. Her collaborations—whether in the haunting textures of Titanic, her project with Héctor Tosta, or the stark intimacy of her 2022 solo album Se Ve Desde Aquí—defy categorization.

“If I don’t know who I can be, then I am my feeling,” Fratti declares in the opening track of Vidrio, her collaborative album with Tosta (also known as I La Católica). Released under the moniker Titanic, Vidrio was one of three albums Fratti released in 2023, a testament to her restless creative energy and widespread resonance. Whether in solo work or collaborations, her music is rooted in transformation—of sound, of self, of the structures that define musical expression.

Here, the underground’s adoption of classical techniques isn’t nostalgia; it’s about reclaiming sound as something fluid, immediate, and unbound by expectation. It is the soundtrack of young creatives redefining the landscape in Mexico today. The cello, in the hands of Mabe Fratti, is neither an artifact nor a novelty, but a force—urgent, alive, and attuned to the city’s evolving pulse.

What lies beneath: the living archives of Lorena Mal

by Ambika Subra.

Unearthing the hidden narratives beneath our feet, Mexican artist Lorena Mal is revealing the deep entanglements between land and power. She is an excavator—not only of the earth’s soil and trees, but of the knowledge systems, political structures, and forgotten narratives embedded within it. Working across sculpture, performance, and archival intervention, Mal dismantles the illusion of landscape as a neutral backdrop. Instead, she exposes it as a charged site of conflict, migration, and resilience, shaped by forces both geological and geopolitical. One of the most exciting voices in contemporary Mexican art, her recent works at the XV Bienal FEMSA and Museo Jumex have cemented her place as a radical force in rethinking our experiences of landscape.

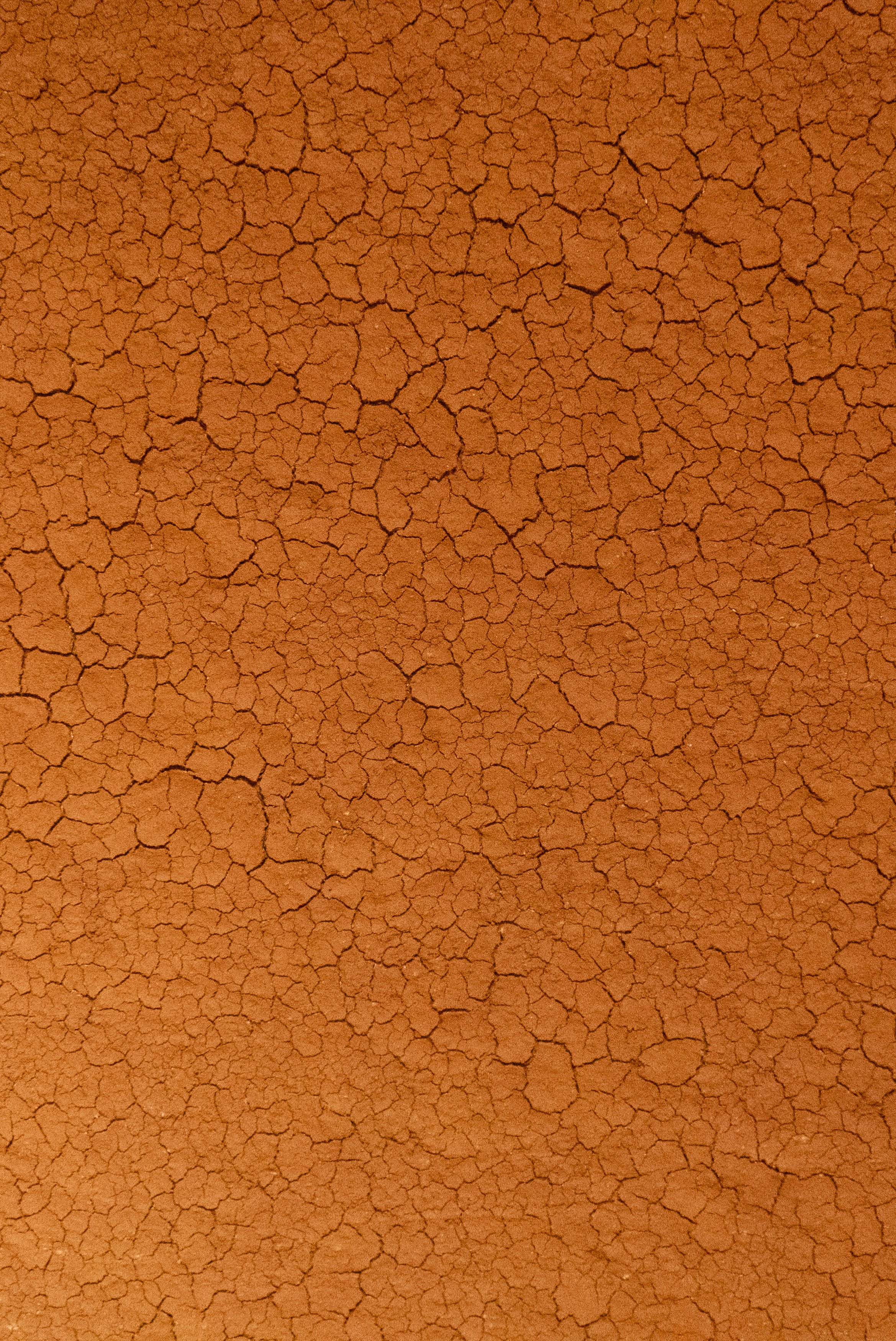

Mal refuses to see land as separate from history. In Restregarnos Tierra en los Ojos, an installation commissioned for the XV Bienal FEMSA, she created an archive of occupation and displacement by covering the space’s surfaces with soil—a raw, living material applied in a fermented state, allowing microbial life and air to bind it into a clay that naturally cracked and shifted over the four months of the exhibition. Sourced from the Bajío, the soil bore the region’s long past of floods and droughts, colonial mining extraction, and environmental destruction. Who has the right to a land? Who determines its fate? Mal’s intervention blurred the lines between architecture and archaeology, embedding the region’s instability directly into the walls of the exhibition. The soil itself became testimony—not just a metaphor, but an active record of conflict, survival, and resistance.

Beyond the visible, Mal’s work listens. In Largo Aliento, performed at Museo Jumex this past year, she translated tree rings into sonic compositions, using instruments made from those trees as a vehicle for a deep, resonant breath. Just as the soil preserves and reveals the memory of land through its raw materiality, Largo Aliento treats breath as a conduit for memory, where tree rings vocalize their silent histories. These rings, like layers of sediment, hold the imprints of environmental upheavals—fires, droughts, cycles of violence and renewal. By playing their breath, Mal does not impose a structure onto their histories but coaxes out their latent recollections, turning them into sound. Her instruments do not adhere to tempered scales or fixed notation, but instead respond to human interaction. This relationship resists linear time in favor of something more fluid and horizontal, creating a resonance that blurs the boundary between past and present. Both earth and breath become modes of listening—fragile yet persistent archives of what landscapes remember.

History is not confined to human narratives alone. At its core, Lorena Mal’s work is about destabilization—of narrative, of power, of our very understanding of place. She is not interested in transformation as a fixed act but in how landscape holds and reveals its own records through its raw architecture. Mal excavates how land bears witness to colonial displacements, migrations both human and botanical, and the erasure embedded in plantation histories. By blending materials across geographies, carving new sonic pathways through time, and forcing us to confront what lies beneath our feet, Mal reframes the land as an active force—one that remembers, resists, and refuses erasure. Her practice is not simply an exploration of landscape; it is a reconfiguration of how we engage with the world itself.

re/presentare is rewriting the role of architecture in Mexico

by Ambika Subra.

In Mexico, power is etched into the streets—highways slice through working-class neighborhoods, glass towers rise from Indigenous communities. Architecture in Mexico can serve as both a weapon and a witness to inequality. But re/presentare, a new spatial research agency in Mexico City, based at UNAM, is attempting to flip the script. Founded by architects Sergio Beltrán-García and Elis Mendoza, and working as part of Investigative Commons - a network of agencies around the world using open-source methods to investigate human rights abuses - re/presentare is moving beyond analyzing space. Its architects are trying to reimagine space as a tool for justice, hope, and collective action. This year, with the launch of their first major socio-environmental investigation in Mexico City, their work is set to establish a new benchmark for spatial research and intervention.

“Architecture is the discipline of organizing bodies,” Beltrán-García says. “You can pass here; you cannot pass there. And that means power.”

Both Beltrán-García and Mendoza were trained by Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture, the renowned London-based investigative group based at Goldsmiths, University of London. But while Forensic Architecture excels at producing analytical data sets for the purposes of exposing state and corporate violence, re/presentare looks to go a step further—into direct intervention and localized action. Their goal is not just to diagnose problems but to collectively repair and redesign spaces to amplify communities over individuals and capital.

One of re/presentare’s first major investigations is taking place in Xochimilco’s San Gregorio Atlapulco, a pueblo originario where locals have been resisting water privatization and urban expansion for several years. Beyond research, the team is working in collaboration with the community to develop methods for investigating the violence they have faced at the hands of the state, including the erasure of their collective traditions. “Investigating collectively,” Mendoza emphasizes, “is just as important as resisting collectively.”

In this way, it’s helpful to understand them not just as architects but as storytellers. They’re using design to make invisible violence visible. “The violence is in the silence,” Mendoza says. “Our job is to force it into the light.” Re/presentare is developing a new vocabulary of resistance through physical and digital interrogation: How do you map the chaos of social media, YouTube comments, or the calculated rhetoric of a morning press conference? How do you make power visible?

Solutions come through building networks. With their work in Xochimilco, alongside local land and water defenders, a model of cooperation is forming that challenges architecture’s often individualistic and hierarchical structures. It’s a horizontal approach which lays groundwork for future expansions, such as collective exhibitions with other spatial practitioners—architects, artists, and individuals from entirely different disciplines. “It’s not enough to analyze what we see,” says Beltrán-García. “We also have to visualize it, to make it tangible in museums, workshops, and public forums.” Through workshops, collaborative design projects, and on-the-ground interventions, re/presentare is creating a new kind of research practice—one that merges community engagement with the transformation of public space.

Mexico is a country facing acute problems with gender violence, environmental destruction, and authoritarianism, all of which is reshaping the country’s physical and built environment. re/presentare is working to imagine and build alternative futures. “The only way to build the future we want,” Mendoza insists, “is by strengthening our networks. By working together.” With this upcoming investigation in Mexico City, their practice holds the power to flip the script—turning Mexico’s struggles into strength via its collective action. In the face of overwhelming challenges, re/presentare is paving the way for another possible outcome where space is not a tool of oppression, but a canvas for hope.